POSITIVE MONEY

Believe it or not, Russia isn’t worried about falling oil prices. Here’s why…

By Marin Katusa, Chief Energy Investment Strategy Dec 14, 2014.

By Marin Katusa, Chief Energy Investment Strategy Dec 14, 2014.

Recent Articles

Courtesy of the Venus Project

Minority rules:

Scientists discover tipping point for the spread of ideas

Scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have found that when just 10 percent of the population holds an unshakable belief, their belief will always be adopted by the majority of the society. The scientists, who are members of the Social Cognitive Networks Academic Research Center (SCNARC) at Rensselaer, used computational and analytical methods to discover the tipping point where a minority belief becomes the majority opinion. The finding has implications for the study and influence of societal interactions ranging from the spread of innovations to the movement of political ideals.

CLICK HERE for more

What this means is we only need 10% of the population to understand how these few individuals are robbing us and enslaving us to transform the narrative society believes in, to stop them.

Scientists discover tipping point for the spread of ideas

Scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have found that when just 10 percent of the population holds an unshakable belief, their belief will always be adopted by the majority of the society. The scientists, who are members of the Social Cognitive Networks Academic Research Center (SCNARC) at Rensselaer, used computational and analytical methods to discover the tipping point where a minority belief becomes the majority opinion. The finding has implications for the study and influence of societal interactions ranging from the spread of innovations to the movement of political ideals.

CLICK HERE for more

What this means is we only need 10% of the population to understand how these few individuals are robbing us and enslaving us to transform the narrative society believes in, to stop them.

Oil is not quite as powerful a weapon against modern-day Russia as one might think.

By arguing that the slump in oil prices will finish off Russia just like it did the Soviet Union, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, writing in the Daily Telegraph, is forgetting how far Russia has come since those dark days.

It is true that the USSR couldn’t cope with falling oil revenues and that Saudi Arabia is credited with helping to break up the former empire by dramatically increasing oil production from 2 million to 10 million barrels per day in 1985.

And sanctions could make it harder for Russian firms to access Western know-how, and ultimately affect Russia’s oil output.

But that’s only if they drag on for years—which is doubtful, given the price the EU is already paying. A cut in global oil supply—and stronger global growth—will likely rebalance the oil market in the meantime.

A measure of Russia’s improved prospects is that the population is growing again for the first time since 1992. In fact, sanctions notwithstanding, Russia’s finances look pretty stable for now.

Russia has only about $678 billion in foreign debt, which it’s been vigorously paying down from the high of $732 billion reached at the end of 2013. (The US debt to foreigners has passed $6 trillion, and it’s growing.) It’s running a record-high budget surplus and a positive balance of payments. And it’s circumventing the dollar through trade deals. Even after spending $60 billion propping up companies starved of dollar liquidity, Russia has nearly $375 billion of foreign reserves.

Although GDP growth has slowed from 2012’s torrid 4.25% pace, it’s still projected to come in at 1%, no worse than 2013.

Furious about being locked out of SWIFT—the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, which helps facilitate international financial transactions—Putin has also ordered the Russian central bank to proceed with building its own national payment settlement system as an alternative.

Then there’s “Project Double Eagle,” which will enable trade partners to price oil in gold. That will allow users to move away from the dollar (and the euro), and conduct their business in something physical and more substantial than fiat money—and Russia’s fellow BRICS nations (Brazil, India, China and South Africa) are cheering it on.

So, perhaps there’s method in Putin’s madness. Russia has not only substantially increased gold production but is stockpiling the stuff, doubling its reserves between 2008 and 2014.

It’s true that the country’s budget was based on oil prices of $96 per barrel. With oil sinking below $70, that hurts for certain. But Russia will survive. It will do some belt-tightening. And it gets a boost from the falling ruble—which is down 25% against the dollar just since the end of September—because that helps to offset losses from cheaper oil.

Russian oil companies earn dollars abroad for their exports, but spend rubles domestically. That means that their extraction budgets remain unaffected and, additionally, it ensures that government tax receipts won’t drop precipitously. Production actually rose to 10.6 million barrels per day in September, close to the highest monthly figure since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Russia’s 8 million barrels of daily export account for 15% of the total oil moving in world markets.

Ironically, Obama’s sanctions could have worse consequences for the US. If Russia ramps up production in order to raise revenues, that will lead to an even bigger fall in oil prices. And one of the primary victims will be US shale production. US fracking operations—which are more costly than conventional Russian (or Saudi) drilling—begin to get uneconomical below $70 per barrel. If the price drops to $60, many US unconventional wells will have to shut down and imports will rise once again.

Thus, the slide in oil prices threatens American energy independence and emboldens rather than weakens Russia.

Meanwhile, Russia forges ahead with exploration and infrastructure development. Putin just inked a 25-year oil deal with China that includes the construction of a brand new 3,000-mile pipeline. And he’s sending fleets of nuclear-powered icebreakers into the Arctic to stake out more reserves, along with troops to protect them.

While Americans are counting the few dollars they’ll save on gasoline now and spend on gifts this Christmas, Putin is counting all the billions he’ll make when oil rebounds.

Russia may or may not be losing the current battle. But no matter what Evans-Pritchard may think, Putin has no intention of losing the war—in fact, he’s the only one who really understands what the ultimate prize for winning it is.

As my new book, The Colder War, makes clear, the geopolitics of energy—especially the struggle between Russia and the US—is the single most important force in the world today.

Putin’s not going to spare any effort to come out on top, and the smart money isn’t betting against him. This would not mark the first time he has been wounded and come back stronger.

By arguing that the slump in oil prices will finish off Russia just like it did the Soviet Union, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, writing in the Daily Telegraph, is forgetting how far Russia has come since those dark days.

It is true that the USSR couldn’t cope with falling oil revenues and that Saudi Arabia is credited with helping to break up the former empire by dramatically increasing oil production from 2 million to 10 million barrels per day in 1985.

And sanctions could make it harder for Russian firms to access Western know-how, and ultimately affect Russia’s oil output.

But that’s only if they drag on for years—which is doubtful, given the price the EU is already paying. A cut in global oil supply—and stronger global growth—will likely rebalance the oil market in the meantime.

A measure of Russia’s improved prospects is that the population is growing again for the first time since 1992. In fact, sanctions notwithstanding, Russia’s finances look pretty stable for now.

Russia has only about $678 billion in foreign debt, which it’s been vigorously paying down from the high of $732 billion reached at the end of 2013. (The US debt to foreigners has passed $6 trillion, and it’s growing.) It’s running a record-high budget surplus and a positive balance of payments. And it’s circumventing the dollar through trade deals. Even after spending $60 billion propping up companies starved of dollar liquidity, Russia has nearly $375 billion of foreign reserves.

Although GDP growth has slowed from 2012’s torrid 4.25% pace, it’s still projected to come in at 1%, no worse than 2013.

Furious about being locked out of SWIFT—the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, which helps facilitate international financial transactions—Putin has also ordered the Russian central bank to proceed with building its own national payment settlement system as an alternative.

Then there’s “Project Double Eagle,” which will enable trade partners to price oil in gold. That will allow users to move away from the dollar (and the euro), and conduct their business in something physical and more substantial than fiat money—and Russia’s fellow BRICS nations (Brazil, India, China and South Africa) are cheering it on.

So, perhaps there’s method in Putin’s madness. Russia has not only substantially increased gold production but is stockpiling the stuff, doubling its reserves between 2008 and 2014.

It’s true that the country’s budget was based on oil prices of $96 per barrel. With oil sinking below $70, that hurts for certain. But Russia will survive. It will do some belt-tightening. And it gets a boost from the falling ruble—which is down 25% against the dollar just since the end of September—because that helps to offset losses from cheaper oil.

Russian oil companies earn dollars abroad for their exports, but spend rubles domestically. That means that their extraction budgets remain unaffected and, additionally, it ensures that government tax receipts won’t drop precipitously. Production actually rose to 10.6 million barrels per day in September, close to the highest monthly figure since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Russia’s 8 million barrels of daily export account for 15% of the total oil moving in world markets.

Ironically, Obama’s sanctions could have worse consequences for the US. If Russia ramps up production in order to raise revenues, that will lead to an even bigger fall in oil prices. And one of the primary victims will be US shale production. US fracking operations—which are more costly than conventional Russian (or Saudi) drilling—begin to get uneconomical below $70 per barrel. If the price drops to $60, many US unconventional wells will have to shut down and imports will rise once again.

Thus, the slide in oil prices threatens American energy independence and emboldens rather than weakens Russia.

Meanwhile, Russia forges ahead with exploration and infrastructure development. Putin just inked a 25-year oil deal with China that includes the construction of a brand new 3,000-mile pipeline. And he’s sending fleets of nuclear-powered icebreakers into the Arctic to stake out more reserves, along with troops to protect them.

While Americans are counting the few dollars they’ll save on gasoline now and spend on gifts this Christmas, Putin is counting all the billions he’ll make when oil rebounds.

Russia may or may not be losing the current battle. But no matter what Evans-Pritchard may think, Putin has no intention of losing the war—in fact, he’s the only one who really understands what the ultimate prize for winning it is.

As my new book, The Colder War, makes clear, the geopolitics of energy—especially the struggle between Russia and the US—is the single most important force in the world today.

Putin’s not going to spare any effort to come out on top, and the smart money isn’t betting against him. This would not mark the first time he has been wounded and come back stronger.

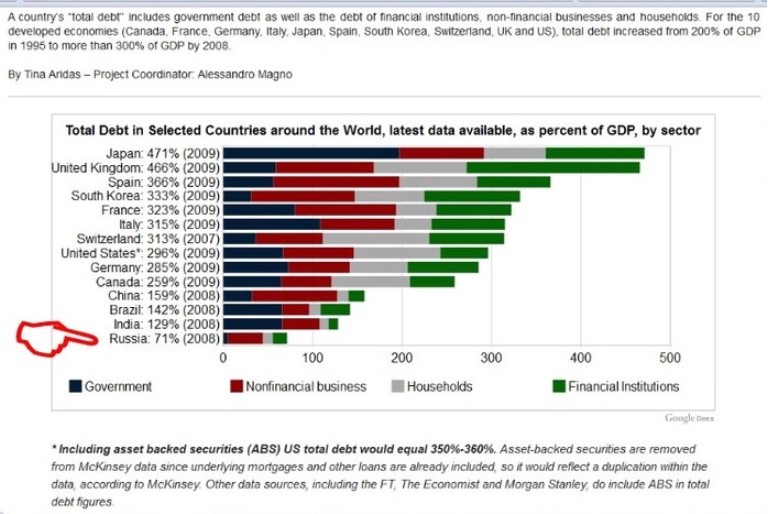

The Russians have learned the way the financial CABAL that controls

the US and the EU, do it through DEBT.

So they have been careful to pay most of their foreign debts and stop using the US dollar.

The chart below shows Russia as the least indebted nation, especially Government Debt.

the US and the EU, do it through DEBT.

So they have been careful to pay most of their foreign debts and stop using the US dollar.

The chart below shows Russia as the least indebted nation, especially Government Debt.

Source ING: Bloomberg

Over the course of this year Russian government debt has been solid against a volatile global backdrop, with a decades worth of generally tight fiscal policy and strong oil revenues, backing Russia’s debt position. Uralsib’s Dudkin believes that despite the prospect of increased outlays over the course of the coming year, commitments to rein in the budget deficit will buoy debt markets.

“This years performance is mainly due to a balanced budget policy in Russia, with the Government keeping its expenses under control. But in 2012, the year of elections, military expenses and some social spending will go up. Anyway, according to Russia’s Finance Minister Alexey Kudrin, who is always conservative, the government debt won’t exceed 3% of GDP in 2012.”

That sentiment was echoed by ING’s Fedorov who noted “After the crisis in 1998 Russian authorities just put balancing the level of Government debt in focus and was pretty careful with budget spending,” adding that once the key immediate driver is the rouble, with a debt rebound when crude prices and the rouble stabilize.

“I think the negative price trend will follow the rouble on FX markets, but when the rouble and Brent crude stabilise it will be strong signal to buy.”

Over the course of this year Russian government debt has been solid against a volatile global backdrop, with a decades worth of generally tight fiscal policy and strong oil revenues, backing Russia’s debt position. Uralsib’s Dudkin believes that despite the prospect of increased outlays over the course of the coming year, commitments to rein in the budget deficit will buoy debt markets.

“This years performance is mainly due to a balanced budget policy in Russia, with the Government keeping its expenses under control. But in 2012, the year of elections, military expenses and some social spending will go up. Anyway, according to Russia’s Finance Minister Alexey Kudrin, who is always conservative, the government debt won’t exceed 3% of GDP in 2012.”

That sentiment was echoed by ING’s Fedorov who noted “After the crisis in 1998 Russian authorities just put balancing the level of Government debt in focus and was pretty careful with budget spending,” adding that once the key immediate driver is the rouble, with a debt rebound when crude prices and the rouble stabilize.

“I think the negative price trend will follow the rouble on FX markets, but when the rouble and Brent crude stabilise it will be strong signal to buy.”

Source BLOOMBERG

“The state of Russia’s public finances has improved dramatically since then, making a government default in the near future highly unlikely. That said, if oil prices stay at current levels over the next decade, government debt will reach a level at which investors may once again start to worry about the sustainability of Russia’s public finances.

There are three key reasons why the unfolding crisis in Russia is less likely to culminate in a government default than in 1998. First, the overall debt level has fallen substantially over the past 15 years. By the end of 1997, Russia’s total government debt stood at around 50% of GDP, compared with just 13% of GDP today. Second, … a major factor that contributed to the 1998 default was the high level of short-term debt. By contrast, the level of short-term government debt in Russia is now minimal. This means that rollover risks are low. Third, … Russia’s FX reserves currently stand at $420 billion (20% of GDP), compared to just $17 billion (5% of GDP) at the end of 1997.”

“The state of Russia’s public finances has improved dramatically since then, making a government default in the near future highly unlikely. That said, if oil prices stay at current levels over the next decade, government debt will reach a level at which investors may once again start to worry about the sustainability of Russia’s public finances.

There are three key reasons why the unfolding crisis in Russia is less likely to culminate in a government default than in 1998. First, the overall debt level has fallen substantially over the past 15 years. By the end of 1997, Russia’s total government debt stood at around 50% of GDP, compared with just 13% of GDP today. Second, … a major factor that contributed to the 1998 default was the high level of short-term debt. By contrast, the level of short-term government debt in Russia is now minimal. This means that rollover risks are low. Third, … Russia’s FX reserves currently stand at $420 billion (20% of GDP), compared to just $17 billion (5% of GDP) at the end of 1997.”